Culture in the Wake of the Kuwaiti Oil Boom

A conversation with Farida Al Sultan

kaelen wilson-goldie, fatima al qadiri

Before Doha, Dubai, or Abu Dhabi, the city with the boldest ambitions in the Gulf may have been Kuwait. In the 1970s, everyone from IM Pei to Andy Warhol traveled here to build, show, experience, and experiment in an atmosphere that was flourishing, at least in part, care of a sudden oil boom.

There were poetry readings, public performances, avant-garde fashion statements, and much more. Official and independent arts infrastructures were taking shape, thanks to the influx of cash and waves of influence rolling in from Beirut and Bombay and Baghdad.

The Sultan Gallery, which opened in 1969, is a living archive of those times, the history of which is unknown by many and overlooked by others. Farida Al Sultan first got involved in her early twenties, when her older brother and sister were running the show. She convinced them to keep going when the political situation started shifting in Kuwait, even when the arts seemed totally abandoned during the Iraqi invasion.

Today, Al Sultan not only directs the gallery, she also steers its original vision through a markedly different cultural landscape. Kuwait is no longer the hot spot it once was, but the Sultan Gallery is still a place for gathering young talent as well as a site for elaborating new aesthetics and ideas. Al Sultan, who is conscientious and enormously down to earth, met with Bidoun in several different cities to discuss the past, present, and future of the place she hopes all of her artists and audiences will think of as home.

My parents moved from Kuwait to Bombay before the oil. There were many Kuwaiti families living there at the time. My family’s business was general trading — spices, wood, rice. We’re a family of nine. Five of us were born in India, four in Kuwait. As a child, I went to a missionary school run by nuns, where I studied French, English, and three Indian dialects. We studied Arabic on the weekends, which is when we met up with kids from other Kuwaiti families.

The building where we lived in Bombay was called Shah-Bagh on Peddar Road and was inhabited primarily by Indians. It was four or five stories high and built in the art deco style. It was also just one block away from the Cadbury factory, so you could occasionally smell chocolate in the air. Across the street from us was a Hindu temple, and outside of it were trays of marigold garlands and coconuts to offer to the gods. On one floor was a family involved in the film industry — the parents were producers and the children, actors — and we used to play with the kids. Many of them later became well-known, such as Nutan and Tanuja.

After the discovery of oil and the creation of positions within the Kuwaiti Oil Company, we all moved back. It was 1959, and I was thirteen. Because none of us really spoke Arabic — we spoke English and Hindi — and there were no secondary schools, many of us had to go to places like Cairo to study, as I did, or further abroad, like my brother, who went to Scotland to study medicine. Eventually I finished high school and university in Beirut. When I came back to Kuwait later, I taught English at a high school and later at university.

My brother Ghazi opened the gallery in 1969 on Fahad Al Salem Street in the Qibla district of Kuwait. The Gulf was just opening up then, and Kuwait was especially open. Even before the discovery of oil the country was culturally oriented because it was a nexus of many trade routes to the far east. There were poetry readings all the time, and the arts council was very active then. Kuwait was the place to be. The first emir of Kuwait was a visionary. There was a time when we had the highest rate of literacy in the world. We had a master plan, and a constitution that limited the power of the ruling family. You know, even before there was oil, there was culture. The first school in Kuwait, the Al-Mubarikiya School, opened in 1912. It concentrated on Arabic and math and was unlike the earlier Qur’anic schools. An important poetry magazine was launched in 1928, too.

Ghazi had studied architecture at Carnegie Tech and then later went on to Harvard. It was the very beginning of the art scene, and he showed only Arab and local artists at the gallery. There were no other galleries at the time, probably not even in the Gulf. There were annual group exhibitions organized by the American Women’s Association as well as the Fine Arts Society in the ’60s, but no galleries yet.

Ghazi gave me a corner of the gallery for crafts. And so I went back to India and began commissioning artisans to work on embroidered cushions. Later, during my travels abroad to England, I would frequent graduate shows of some of the art schools and commission artists to make pots for the garden and house, or ask weavers to do general basketry work. I also met up with and visited the studios of many Arab and English artists.

Back in the Sixtiess and Seventies, the Kuwaiti government supported the arts financially, and even sent artists abroad to study. Artists mainly gathered at the Sultan Gallery or the Marsam Al Hur (The Free Atelier), which was an old Kuwaiti mud-house complex founded by the Ministry of Education in 1960 and was basically a series of studios for artists in a traditional architectural setting. The government awarded full-time salaries to thirty artists, mostly educated abroad and selected by an annual committee. It was later run by the Ministry of Communication, and then later, the national arts council.

Kuwait was also active in the fields of architecture, design, film, and fashion. Students used to come to Kuwait to study music and theater. Architecture was also changing, beginning with the 1960s, when it became more experimental and regionally influenced — by Egyptian, Lebanese, Palestinian, and English architects. My brother Ghazi was influential in bringing architects to Kuwait in the 1970s. He brought George Candilis, IM Pei, Sasaki, and others. He even began a waterfront project called the Green Island, which was an artificial island, an aesthetic folly. When I see other countries bringing architecture to the Gulf now, I think to myself, “Been there, done that.” But unfortunately, there’s a lull in activity today in Kuwait.

Of course, everything was affected by the oil boom of the Seventies and the stock market crisis of 1982. People started sending their children abroad for school. When people traveled, they would bring back magazines like Hawwa’magazine from Egypt, and Life, and we would discuss them. We also started importing art materials — paints, brushes, clay — and art teachers, for that matter — Egyptian, Syrian, Palestinian. Most of the art teachers were Egyptian. They were the only people in the region who ever really had art schools.

I would say that Munira Al Qadhi was the most important Kuwaiti artist of those times. Her works are in major museums abroad. She had studied at the Central School of Arts and Design from 1959 to 1961 in London. Her show with an Iraqi artist and architect named Essam Al Saidin in 1969 at Sultan Gallery was not only the first show to be held at the gallery but also the first major art show held in the Kuwaiti private sector. A Kuwaiti printmaker and graphic artist, Munira was a member of the Arab Art Group and actively exhibited in Europe and the Middle East during the Sixties and Seventies. I remember Munira had spiky hair. She was a real eccentric. Her work was very much in the school of symbolism, some torn canvases revealing various things behind them, an abstract series of mothers and such. She’s a recluse now, unwell, creating digital art, and lives alone in a flat in the Marzouk Pearl building by the sea.

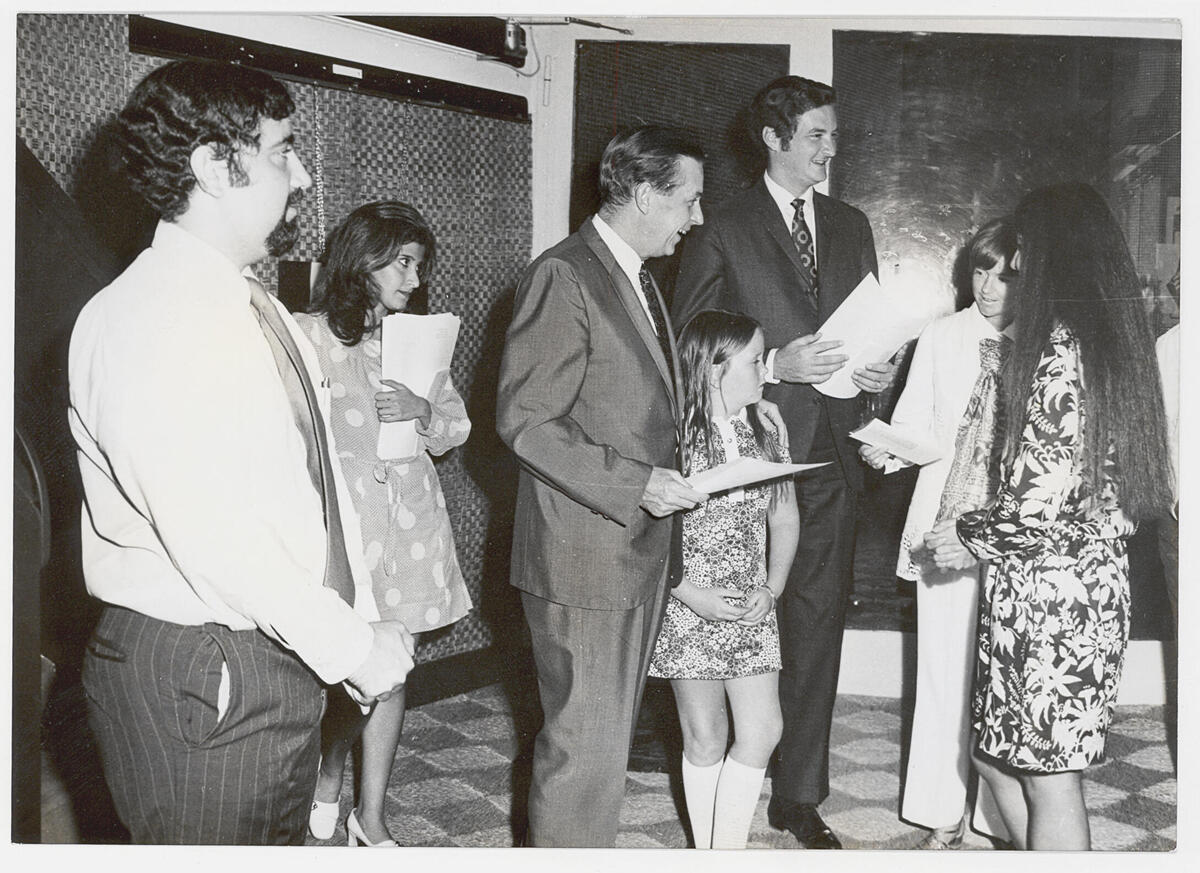

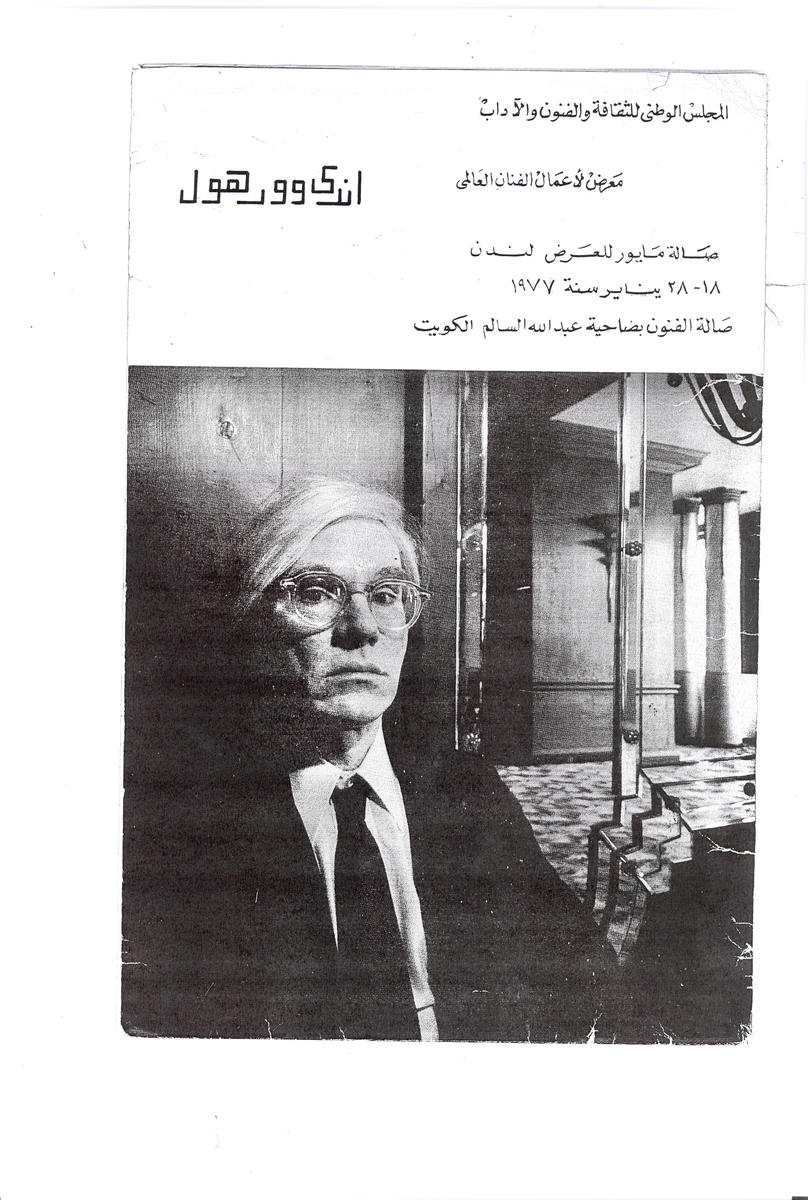

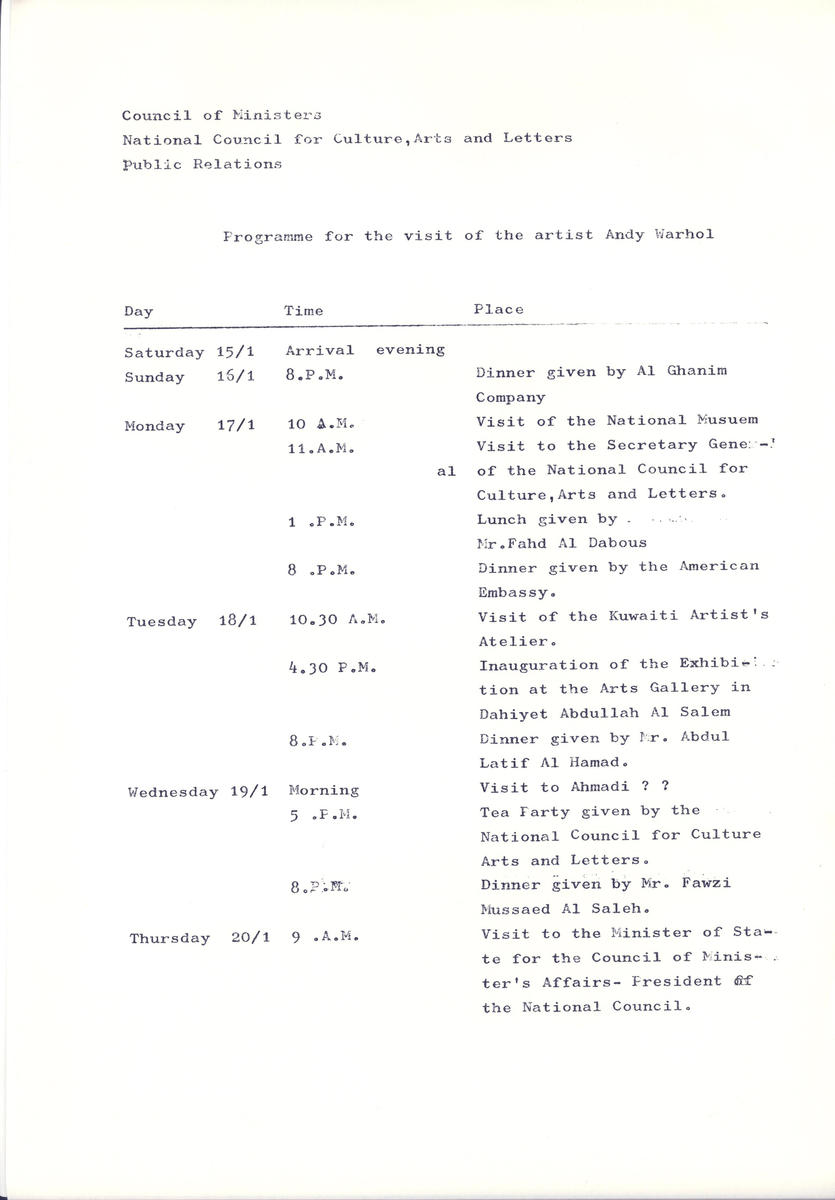

Andy Warhol came to Kuwait in 1977, invited by the National Council of Arts, Culture, and Letters, and an exhibition of his work was held at the Dhaiat Abdullah Al Salem Gallery on January 18, 1977. Fred Hughes, his manager, accompanied him from the States, along with James Mayor of the Mayor Gallery in London. My sister Najat had initiated the meeting. I was heavily pregnant, but I do remember that he was a man of few words, standing in a corner all by himself, though you could tell that visually he was recording it all. The turnout at the opening was huge. The next night I went to a dinner for him at my sister Fawzia and Fawzi Mussaed Al Saleh’s house, where the wine and champagne were flowing. Warhol was a guest of the Kuwaiti state for a week. In the exhibition, he showed the Marilyn, Mao, electric chair, soup can, and early and recent flower prints, along with some drawings. It was a thrill for people who studied abroad to have this icon in Kuwait, but for the most part, people didn’t know him. Today, Sheikh Mubarak Fahad Al Salem Al Sabah has a row of Marilyns in his house, I have an electric chair print, and so do other members of my family.

I think the Sultan Gallery helped lay a foundation for the collecting of fine art in Kuwait. There are people who have bought one piece from every show the gallery has had since 1969. There was a collecting culture in the 1960s and ’70s, and the gallery even restricted collectors from buying more than one piece of art at a time! That was how different things were. Collectors included my uncles, a few people in the oil sector, some people from embassies. Later on, collectors emerged, such as Abdul-latif Al Hamad, who was buying for the Kuwait Fund, and others started buying for banking institutions, like Aziz Sultan, the CEO of the Gulf Bank. The national arts council also started collecting the work of any artist exhibiting through their organization, which culminated in the establishment of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Kuwait.

There have been biennials in Kuwait, but they have been awful. Take for example the Qurian Festival, which started in the Eighties and is actually not a biennial but an annual monthlong cultural festival that includes an art exhibition and competition. There’s also the Al Khorafi biennial, which is fairly new, about six years old, and open to all Arab artists. Anyway, a lot of the time when you have exhibitions sponsored by the government, it’s not on a par with privately run events. They don’t clean. They don’t paint the walls. The work is not great.

Oh, and there was the Saddam biennial in Iraq, which started in 1986 and was open to artists from around the world. The biennial featured lectures, murals, publications, and more. About twenty Kuwaiti artists were invited in 1986. The last Saddam biennial was supposed to be in October 1990, and a number of Kuwaiti artists had submitted work by April of that year. The biennial was cancelled after the invasion of Kuwait in August and, as it happens, none of the artists got their work back. Najat and Ghazi had traveled to biennials in Baghdad in the early Seventies to source out, meet, and commission artists. Up until then, Iraq had been Kuwait’s big brother, culturally speaking, in terms of art and music.

In 1980, my brother decided to close the gallery. I told him he couldn’t. He said, “Fine, you and Najat do it.” Najat was very much involved up until the invasion in 1990. I was more involved in accounts and she was more the brains behind the gallery. She passed away of breast cancer thirteen years ago.

When the Iraqi invasion took place in August 1990, I was in Boston. My husband called that same day to tell me not to come back, and that he would be sending my son Rakan, who was with him, out to meet me in London. I finally came back to Kuwait in 1991 with the children, got back to work helping my husband set up his business, and helped to restart the school that the children had been attending.

Today, I like to encourage young artists through the gallery. The shows I’m most proud of are those of Kuwaitis such as Ghada Alkandari, Fatima Al Qadiri, Khalid Al Gharaballi, Nadia Al Foudery, and others. Photographs and watercolors are my favorite mediums. A couple of times a year I do photography shows, such as a recent group show by Iranian artists, including Bahman Jalali. I’ve also shown Egyptian artist Moataz Nasr and Moroccan artist Lalla Essaydi, and we are steadily building up a clientele who appreciate the medium. Sometimes I offer younger artists the chance to curate the space.

Today, the Sultan Gallery is close to the airport, whereas in the past we used to be in the city. We’re situated in a low-built industrial area subsidized by the government for factories, like those for paper manufacturing or water bottling. It has become a destination in that it’s a little bit out of the way, like the Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut, so only people appreciative of art seek it out.

The problem with galleries in Kuwait nowadays is that they compromise too much to commercial interests — for example, renting their spaces in between art shows to local designers who sell their kitsch homemade clothes or rugs. Because art is not a hugely profitable business, a lot of the galleries cease operating. There is little press culture, too. Sometimes one has to lure the press with gift packages, which I don’t encourage. Magazines like Men’s Passion, edited by Simon Balsom, and Bazaar, edited by Ahmed Adly, and the newspapers Al-Watan Daily(which has the Herald Tribune supplement and is edited by Dina Al-Mallak) and Al-Awan in Arabic are some of the few that come willingly to cover the exhibitions. Art not being a priority has forced much of the press to close down their cultural sections.

Kuwait has changed a lot. Starting in the 1980s, Islamists began smashing public sculptures. Universities are no longer coeducational, and there is talk of regular schools following their lead. Whereas in the past, a cousin of mine, Fatima al-Hussein, went out in the street and burned her abaya in protest against women’s oppression, we are now regressing! There are no formal art schools, probably because of a fear of the human form, or nudes. Look at the great art coming out of Iran! We don’t need nudes. There was a time when Kuwait stood to be a pioneer in the region. Those times have passed.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Always great to hear from you :O)